By Tina Jasperson

This project began with a film, and you felt wasn’t finished, which prompted the book. At the end of the book, you say your greatest revelation is accepting that there is no end, just a new path. What’s next on your path?

After finishing the film, I had spent so much time researching the feminine and exploring how it revealed itself to me in my own experience, I found that I began to naturally start swinging the other way into the masculine realm. Shortly before the book was released, I spent about a year in NYC working on a business certification in Columbia University, and currently, I’ve continued working hard on a film festival I direct called Literally Short Film Festival, playing short films from all over the world. Curiously enough, now that the book has come out, I’ve been drawn to reading more on Joseph Campbell, Marion Woodman, etc., because I’ve been called to reconnect.

Did anyone say something regarding feminism or their definition during your interview that truly surprised you?

What surprised me the most was what I was faced with at the beginning of the interviewing process. I thought I was making a film about women in feminism, but I came to realize that I was getting confused with the language and the terms. Feminism is a movement about gender equality. On the other hand, the feminine has to do with a way of being, despite your gender, associated with nurturing, creativity, receptiveness, etc. Culturally, we pair this behavior with a sort of weakness; we see it as less important than being factual and structured. To confuse things further, I found that this “feminine” way of being had been historically associated with the female gender. We end up with a world that not only suppresses women for their sex, but also suppresses a behavior that is fundamentally attached to what makes us human beings. This was the most shocking to me because the first time it hit me, it was as if I could just see the chain reaction of a culture that had moved further and further away from understanding its people as emotional beings.

While reading the book, as a self-described feminist, the most surprising thing for me was how hard it seemed to be, almost unilaterally, to pin down the definition of the word feminine itself. Did you expect that to be the case?

Absolutely. Not only was it intentional, but necessary. I recently read this phrase from Joseph Campbell’s book that I absolutely loved. It states, “This doctrine of incommunicability of the truth, which is beyond names and forms, is basic to the great oriental as well as to the platonic traditions. Whereas the truths of science are communicable, being demonstrable hypothesis founded on observable facts; ritual, mythology and metaphysics are guides to the brink of a transcendent illumination. The final step which must be taken by each in his own silent experience.” Returning to defining the feminine, it is a similar matter. The moment you pin down a definition, you take away its transformative power, which is what I am attempting to conserve. I want people who read this book, or who watch the movie, to be able to find their own definition. There are no right or wrong answers.

Here is an example that may help conceptualize it. Imagine an alien comes down to Earth and asks you, “What exactly is a human being?” Perhaps you could respond scientifically and say it is a Homo Sapien from the animal kingdom. Even though true, that answer is only partial to our essence. Perhaps you could say a human being is a live organism with the capacity to love; but again, it doesn’t quite grasp our true nature. There is no black and white answer to such a question. Human beings live in a world of grays. For the alien to understand what a human being is, it would have to meet more than one person, from more than one culture, from more than one age group, from more than one economic context, and so on.

There was a definite removal of “the feminine” from “feminist.” Were you expecting that?

At the beginning, I was not expecting that at all. It took me quite a bit of time to understand what I was actually talking about. I had to ramble for a few months before I began to get my thoughts together. I won’t lie; it can get very abstract. Although, this is why I had to ground it in the topics mentioned in the film: media, body, relationships, men as a gender, professions, and religion. (I think this answer relates to my other answer from question 2!)

You made it a point to talk about how adding a male presence changed things when your brother was along for interviews. Can you talk a little about how this surprised you or wasn’t something you had anticipated – or if you had considered it, can you talk about that?

I’ll start by saying I’m extremely close to my brother, and we love getting into theoretical conversations that, most of the time, lead to absolutely nothing in real life. We even get into heated arguments about stupid things that have nothing to do with anything. It’s just an excuse to spend time together. In any case, this dynamic with him became very important throughout the film because, inevitably, my focus was 100 percent directed towards theoretical conversations, and he was my “go-to” man for discussing these matters. Additionally, we weren’t talking about silly topics anymore. It actually had to do with how we both viewed our lives in the real world and how we behaved towards each other, towards other people, and so on. During our conversations with interviewees, the topic of gender was inevitable, and I saw how his mere presence made everyone go that extra mile to remain objective and true. It just balanced the conversations out. Needless to say, the fact that he is extremely articulate helped tremendously. Looking back on it, I had someone close to me that constantly listened and challenged me in every aspect. I have to add my mother as well, she was indispensable to the entire project.

There are a wealth of experts in each of the categories you chose to focus on: media, relationships, the body, religion, etc. How did you decide exactly who to include in this project?

This was a mixture between research and luck. I spent quite a bit of time reading and researching people from universities, or public speakers, leaders, and so on, that touched on the subject of the feminine. I reached out to many of them. Some accepted, and others did not. In this search though, I bumped into some people in the strangest scenarios that ended up being an amazing addition to the film and book’s narrative. They are happy accidents that currently make me wonder how I would have done it without them. Lastly, there were individuals that I knew I wanted in my film before I even started anything, such as Paula Reeves, Mary Hamilton, James Hollis, Jerry Ruhl, and Patricia Llosa.

You mention that it was important for you to make a space for the younger generation, and I agree. Do you think this is something that’s better portrayed in the film?

I think so. I tried very, very hard to make the film as approachable as possible. In the end, the goal was to bring this theoretical concept down from the world of ideas to real life. Most people don’t think in academic essays on a daily basis, and I wanted to be true to that. I kept using my younger cousins, 14-18 years old at the time, as a point of reference. If I thought they could understand something, I’d go for it. Otherwise, I’d try to simplify it. Even so, there are parts that just couldn’t be filtered any further and I had to accept that as well. In the book, however, I just let go. It was like unleashing everything I held back from the film.

Following up on that, do you think the book would appeal more widely to an older audience and the film to a younger one, based solely on the way people access media at various ages?

Yes. There are always surprises, but I think this was something we all expecting from the beginning.

Who do you most hope reads this book, and what do you hope they take from it?

Of course I’d love for as many people to read the book, not only because it’s any author’s dream, but personally, because I think there is something in there for everyone that could initiate a change towards a better self. Each one of us is responsible for him/herself in this world. The more we understand and accept our inner life and its complexities–give a voice to it–the more we will project a view of wholeness and integration towards our community and towards the rest of the world. It’s not enough to mindlessly go through all the phases of life and follow a path that’s already been written. Change comes from within, and if we do not take the time to truly understand who we are, we will never evolve on a deeper level. Yes, we will see new technologies that go beyond anything we can imagine now, but we will remain primitive at core. What good will technology do if we cannot master the most basic human emotions? This is what I hope the book will spark in my readers.

The political climate feels to have shifted from when you started this project – we have a new president in America; new laws and policies are being proposed for women what feels like daily. How does that change the book’s tone or message? Is it, more or less, relevant?

I believe it’s even more relevant. If you think about the direction this country is moving in, it is starting to rely heavily on fear and ignorance. Fear for the unknown “Other,” whether it be a different sex, nationality, or religious affiliation, and ignorance towards the consequences these actions have towards the people and towards our collective future. I’m personally not a religious person, but I do respect the many truths that religion carries with it. In Christianity, the Bible speaks about how one can only hate something that one does not understand. This couldn’t be more evident in today’s world. Yet how are we to recognize a familiarity in the other, when we have no idea of who we are inside. As humans, we know sadness because we have felt sad before. We know anger because we have been angry before. We know love because we love and are loved. Well, that also stands for the things we do not know. Thus, the more you explore yourself, the greater your vision will become towards others. It’s unfortunate how our culture refuses to see value in what cannot be monetized; and yet, those are the very qualities are what would lead to problems such as gender equality, nurturing our environment, peaceful international relations, public education, and so on.

READ our review of Ensoulment: Exploring the Feminine Principle in Western Culture.

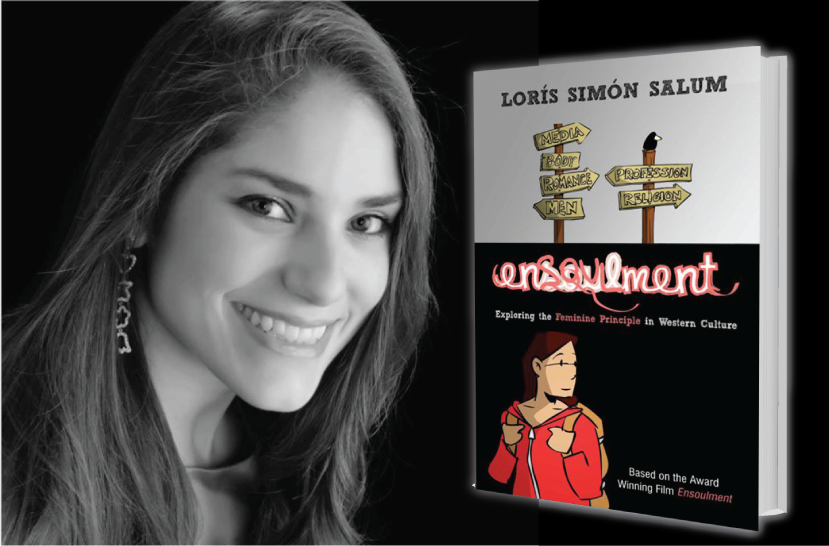

Loris Simon Salum is a 20-something award-winning film director and a published author. Her newest work, a book, Ensoulment: Exploring the Feminine Principle in Western Culture, was just released.

She is an inspiring speaker. In the past year she’s spoken at Jung Center in Chicago; Shell Oil Company in Mexico City; Rice University in Houston; Sam Houston State University in Texas; Claustro Soe Juana University, in Mexica City; and Business and Professional Women’s Group of the Cayman Islands.

Born in Mexico City, she moved to Houston at age 9. She graduated from Rice University with a BA in psychology. Shortly after school, she joined Literal Magazine, where she wrote, directed and co-produced a documentary feature, Ensoulment: A Diverse Analysis of the Feminine in Western Culture. After receiving numerous awards and participating in several worldwide screenings, she opened Literals’ first international short film festival, Literally Short Film Festival.

Last year she earned a Business Certification from Columbia University. She continues to work as director and programmer at Literally Short. She also directed a short film, Diarios de un Desplazado, which premiered at Mexican activist Javier Sicilias’ “Caravan for Peace” in the U.S.

She resides in Houston with her husband. For more information, consult: www.ensoulmentfilm.com.

This page was created by an City Book Review staff member.