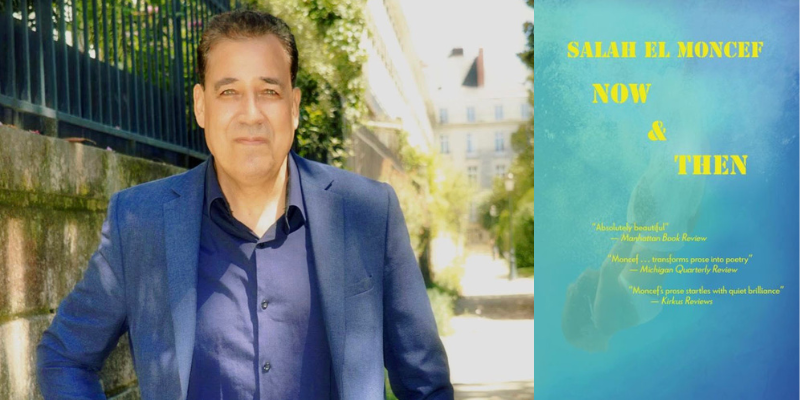

Manhattan Book Review’s Kristi Elizabeth interviews Salah el Moncef, author of Now and Then

What inspired you to write Now and Then? Are any of the stories based on personal experience?

Concerning the inspiration behind Now and Then, I suppose you could say that the book is very much a product of its time. When Penguin Random House contacted me with a potential offer to publish The Offering, they were primarily interested in the stylistic innovations of that novel. What the critics have like about this book, on the other hand, is its social and political relevance. It’s basically an attempt on my part to deal with a number of dark, sinister social forces that are impinging on Europe today, starting with the terrifying popularity of the Great Replacement conspiracy theory among French people, and the political “normalization” of extreme right wing parties that have become integrated in the political mainstream in France and in Italy, with millions of voters endorsing their agenda and giving them unprecedented access to the corridors of power. You know, I arrived in this country from the United States in the late 90s, and I must confess that over the last few years, and for the first time since my decision to settle here, I’ve been feeling genuinely distressed by the political forces of intolerance that are transforming France and Italy today. The collective undercurrent of xenophobic rage behind those political forces is properly terrifying. Then there was, of course, the crisis at the Russia-Ukraine border, culminating with the unspeakable invasion of Ukraine! And so, yes, the stories in Now and Then are a reflection of my personal experience insofar as they’re a way for me to manage all these negative social and political forces pressing on my consciousness—essentially urging me to transform them and sublimate them into something beautiful and instructive to share with my fellow human beings. I suppose that’s what artistic ferment is all about: you take an inner crisis triggered by your social environment, and you transform it into something both beautiful and meaningful. Now and Then was born of a number of social and political concerns that I was trying to get out of my system through the process of writing: the day-to-day effects of intense ethnic tensions here in France, the exponential spread of xenophobia and nationalism in Europe; the increasing threats to democracy and the democratic process itself posed by a number of political figures and their followers.

What was your least favorite part about writing Now and Then?

My least favorite part about writing Now and Then is also the most instructive. I guess it revolves around how I relate to Mariam and how she made me reflect about our relation to time, history, and memory itself. Here we have this astoundingly gifted woman standing between two moments in history: one that is beautifully symbolic, and one that is deeply traumatic. The beautiful historical symbolism she talks about at the beginning of her story is, of course, rooted in the majestic significance of 1976, the year she starts writing her story. It’s the year of the United States Bicentennial, and it’s also the year of the election of a great US President. Well, in thinking about how Mariam is coping with her existence between two completely different societies—a free society celebrating the birth of the greatest democracy in human history vs. a bleakly dictatorial fascist system in Benghazi—well, I found myself reflecting on my position in history, between two time periods and the way I relate to them. Writing Benghazi made me think of my position between the 1990s and today. In engaging that kind of thinking, I found myself doing the same thing as Mariam—only in a diametrically opposed way. While Mariam was dwelling in an island of peace and quietude, trying to come to terms with a turbulent past, I am trying to deal with a chaotic, messy present while constantly comparing it to the late 80s and 90s—years spent in the US and that I consider among the most beautiful, most enlightening years of my life.

There you have it: the most difficult part about writing Benghazi was the most bittersweet one—having to think of the 90s and the egalitarian promise they embodied in relation to our present trials: this abysmal shift the whole world has been witnessing in slow motion from an era of multicultural globalism and hopeful, ebullient egalitarianism for women, minorities, and the LBGTQ+ community to a painfully punishing financial crisis, a tragic pandemic, and now … the horror taking place in Ukraine. The terrifying threats women and the LBGTQ+ community are facing today in terms of their most fundamental, most intrinsic liberties make me very nostalgic about the 90s—and very, very concerned!

Why were you specifically interested in writing about Mussolini? What made you choose this period in time over another for Mariam to reside in?

I chose Mussolini because his populism, his manipulation of the truth, and his appeal to the most negative impulses of humankind are eerily reminiscent of a few contemporary political leaders who are using similar tactics. When I began to brainstorm, I thought it would be interesting to have Mariam “reside,” as you put it, in this era of totalitarianism as a helpless teenager who is being contemplated by an empowered adult “residing” in an era where America is about to celebrate the Bicentennial of the United States and, a few months later, the election of a great political leader who embodies democratic values that are the total opposite of Mussolini’s conception of power. The Italian tyrant believed in violence as an instrument of governance; also the manipulation of the masses by means of untruth and negative, confrontational, polarizing messages that become highly contagious, putting many people in an aggressive frame of mind. Today, we are sadly confronted with similar political figures. Consider this European leader who recently—in a very public, very well-attended speech—spoke at length on the necessity for Europeans to avoid “becom[ing] peoples of mixed-race” (https://wapo.st/3xfAoFQ), and to fend off all kinds of elements of diversity that are, according to him, sapping the foundation of the Old Continent. Honestly, I take these kinds of political postures very personally, and I find the people who express them very scary! I guess writing about Mussolini from the point of a view of pacifist and a feminist is a way for me to manage my fear and outrage—to turn it into something that I can handle creatively and share with my fellow human beings who are equally concerned about the fascist political forces threatening our world today.

Like Mariam, we are similarly in a time of political unrest and turmoil. What do you want your readers to take away from her story regarding our current political division?

Well, I guess a straight answer to this crucial question would begin with one keyword: democracy. An important takeaway from Mariam’s story is that she’s looking back on a thoroughly non-democratic, rigid society from the point of view of an open society about to celebrate the birth of a democracy that became a model for humanity—a model of liberty and equality, of course, but also a model regarding the importance of a system of government based on checks and balances, due process, and the willingness of the many men and women serving their country to stick to the principles of democracy regardless of the risks to their person. Again, the US is a truly magnificent example of how important it is for a society—no matter how ideologically polarized it is—to use the founding principles of democracy as the central moral force that keeps the entire society anchored. There are so many truly heroic men and women in the US today who are saying, Our democracy must remain an inviolable system that defines us all as a society, regardless of our differences.

Which of the characters in your stories do you relate most to? Why?

I love Nausicaa, of course, but I tend to identify more with Mariam—I guess because her sense of identity is diametrically opposite to Nausicaa’s. The narrator of The Night Visitor may not know it, but she’s deeply rooted in what French people call le terroir (one’s home region, with its local specificities). As a French woman who grew up in one of the provinces and not in the capital, like her friend Pauline, Nausicaa is anchored in a set sense of regional and ethnic identity; that gives her a lot of moral strength, of course, but it also makes her very rigid—and vulnerable to difference. That’s why she reacts to Madani’s mere presence with that feeling of visceral revulsion: The calligrapher represents the complete opposite of the regional identity that keeps her moored to her provincial upbringing—he is the ultimate global citizen capable of navigating different cultural environments. That notion of existing between different countries and cultures makes Nausicaa both resentful and scared. Mariam, a woman whose entire existence has been shaped by diversity, starting with the very household in which she was raised, is also the opposite of Nausicaa. I mean, even Mariam’s story is the result of her existing in that in-between state: between two countries, two eras, two cultural systems, etc. I, of course, tend to relate a lot to that state of living between cultures and countries—of being open to the totality of the world, with all its modes of belief, its diversity of gender and ethnic identities. In the full version of Nausicaa’s story (a novel in progress titled Fire Dancers), she moves to the US after her sleepwalking debacle, and discovers the true meaning of open-mindedness and … true love, when she meets a dazzling woman from Ogden, Utah, and decides to enter a new, liberating phase of her life.

In The Night Visitor, Nausicaa declares herself a “post-racial woman,” which quickly becomes complex as she talks about political correctness. What do you want your readers to take away from Nausicaa’s declaration and personal beliefs? Why did you make sure to include these statements in Nausicaa’s character?

It’s very interesting that you focus your question on the concept of “political correctness,” which has different connotations in France. When I first got here I was surprised to discover that the phrase “political correctness” is used by French people to refer to certain restrictions on “authentic” or “free” expression of one’s opinions. It is, of course, unwise to generalize, but as far as questions of ethnicity and cultural difference are concerned, it seems to me that the understanding among many French people of European descent is that “political correctness” inhibits you from expressing “constructive criticism” of people who are ethnically and culturally different—people who happen to think, or behave, or see the world differently from you. I think it’s a widespread belief among many French people—regardless of education—that they are genuinely post-racial; that they are completely neutral, fair, and objective in their treatment of the ethnically different. Therefore, because they see themselves as post-racial, they feel perfectly entitled to express any form of criticism toward ethnically different people. But what if that criticism is in fact emotionally and psychologically biased, if not downright racist? I guess the point I’m trying to make here boils down to this: Saying you’re post-racial, doesn’t make you post-racial. I think that’s the issue with Nausicaa: there is absolutely no measure of self-critiquing in the way she perceives the North African man. At no point does she say, Maybe I’m too biased—or maybe I’m just not equipped, psychologically or intellectually—to understand this man. That kind of wholesome self-oriented skepticism is far more common among Americans, which makes them, despite many tough challenges yet to be surmounted, the nation that is best equipped to manage difference and diversity in all their forms.

Which one of the stories is your favorite? Why?

This is a tough question! Typically, I have a weakness for the more challenging stories, and so I’d say The Night Visitor is probably my favorite, mainly because of the challenges it posed in terms of idiom, style, and structure. The Night Visitor, unlike Benghazi, is a novelette—and as such it doesn’t leave much leeway in terms of letting the narrator take her time to perceive and reflect in detail. When I started thinking about Night Visitor, I knew I had to structure, or plan it, if you will, just like a play or a screenplay—so that I remain as economical as possible in the writing process itself. And so that’s why Nausicaa had to be the kind of narrator who really knows how to cut to the chase. That is an incredibly daunting narrator to live with, because it’s not just about getting right down to it and cutting all the digressive material, it’s also about how is she going to manage to be deeply evocative with very few words, or powerfully poetic in her offhand, informal way. There is also her voice: Nausicaa’s narrative voice is “conversational” from start to finish. That’s a major challenge in terms of maintaining vocal consistency, but also in terms of controlling her vocal rhythms, so that she doesn’t turn monotonous, or strident, etc. Finally, there is what a number of critics didn’t fail to point out: the fallacies of her point of view. Nausicaa is the victim of a lot of subjective distortion in the way she perceives Madani, but she is also brilliantly perspicacious, hilariously mordant, and emotionally vulnerable, deep down. All these elements had to be woven into the textures of her voice—something that was extremely hard to do.

Have you been to Benghazi? If not, how much research did you have to do to be able to write about this place with wisdom?

Yes, I have been to Libya many times with my mom and my siblings, visiting her two brothers in Tripoli and in Benghazi. My family and I were living in Tunis, Tunisia back then, and I’ll never forget that magical period of my life. The weather in that part of the Mediterranean is identical to Southern California weather. I didn’t know it then, but those were the days when Libya wasn’t languishing under the abominable dictatorship of Gaddafi. My mom—who was toughened by many a safari journey, and once even went with my dad and his pearl-diver friends on a pearl-fishing expedition in the Persian Gulf!—would pack us kids into a VW van and we’d drive down along the Tunisian coast to Tripoli. Our uncles were both very wealthy men, so the memories I have of those Lybia vacations were just awesome: In Tripoli, my mom would organize these big spring picnics and we’d go for a daylong jaunt at the ancient city of Leptis Magna. It’s just impossible to describe how beautiful it all was: We’d have the whole place to ourselves, and we’d run and play amid the ruins, and the beach was absolutely sublime. We’d do similar things in Benghazi, with different outings to the beaches, and picnics in the Green Mountain and the ancient city of Cyrene—a city entirely governed by women (hence the symbolism of the figure of the victorious woman hunter that Mariam recalls in Benghazi). Also, both my uncles had stables—that’s where I learned riding, and so that’s an extra beautiful memory. Ultimately, though, in spite of this massive “stock” of images of Benghazi that I have retained from my childhood, writing about that city in the context of the 30s is an altogether different ballgame. A lot of research had to be done—film footage, photographs, and texts. Despite the meticulous research, however, it is ultimately that capacity to project myself in a different era and try to take myself (and the reader!) there in a profound and vivid way: that was very challenging.

At the beginning of The Night Visitor, Nausicaa confesses that she cannot believe she is still talking about Madani. Have you felt a similar way to Nausicaa? Has there been any person or place you have never been able to shake from your mind?

The Bay of Carthage—that’s the one place that will always stay with me. I was raised in a gorgeous French colonial house, about 100 yards from one of the most beautiful beaches on earth. There were lagoons where we could watch the birds and the sea turtles. We fished for octopus and picked mussels. I used to take my horse there and wash him in the seawater. My friends and I would sail all around the bay and we’d often go to the Punic harbor and swim in its deep, cold water, imagining all the spooky things that took place in it thousands of years before. That magical world is just too beautiful for words. You’d have to see it to believe it! I was very lucky to have grown up during a period when those places could be enjoyed peacefully by a group of friends who, without even knowing it, were united in our faith in difference and globalism despite our mindboggling ethnic diversity: we were Jewish and Christian and Muslim; we were Maltese and French and Italian; we were northern European and we were Mediterranean or Middle Eastern. It did not matter at all—we were all united by the miracle that brought us all together under the same sky. Needless to say, part of the not-being-able-to-shake-it-from-my-mind effect is me never ceasing to ask myself: What kind of force intervened to spoil that world irreparably? Still, those beautiful memories linger, and I sure am glad I have them safely locked in my heart…

What is the main takeaway you want your readers to get out of Now and Then? Although there are many themes, what is the one thing you hope all readers get out of these stories?

Bertrand Russell once said: “Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.” I think if there is one takeaway I hope to share with my readers through these stories and essays is that fear of economic uncertainty, of everybody and everything that is different from “us” can often result in an uncontrollable need to create an antagonistic person or group and turn them into the enemy. This is what happened in the 1930s in Europe, of course. People were terrified because of the Great Depression and the abysmal socioeconomic prospects they were projecting for themselves. And so “under the influence of a great fear,” an entire continent succumbs to one of the most destructive, most abject social phenomena: anti-Semitism. Sadly, we know the rest of the story. This, in my opinion, is a historical lesson that is of the highest urgency today. As human beings, collectively, we need to work toward replacing fear of the other, of the different, with love of the other and the different, empathy with them and identification.We need to understand that that fear is very often the result of adverse circumstances that are beyond our control. If we don’t do that, we are literally going to burn Mother Earth to a cinder.

Salah el Moncef was born in Kuwait City, Kuwait. He is the author of The Offering, Benghazi, and Art as Pharmakon. His short fiction, largely focused on the Arab diaspora experience, has been published in numerous British and American magazines and anthologies. He is a five-time Fulbright scholar, a recipient of the Presidential Award for Excellence in the Humanities, and an editor at Routledge. El Moncef is Reader in English and Creative Writing at Nantes University, France.